"... I have more of an emotional attachment for these characters than I thought possible. I don't know what else to say that hasn't been said hundreds of times before so I'll just say thank you. Thank you for revitalizing my love of reading. Thank you for making me see comics as valuable entertainment. Thank you for all the wonderful stories you've given me. And thank you for all the ones you still have to tell. ..."~ "The Walking Dead" reader Jason Winchell writing in to his favorite comics' letter column Letter Hacks with gratitude for the work of writer Robert Kirkman, printed in the back of last week's "The Walking Dead" #92.

Quote for the Week 12/20/11

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

Surprise?

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Thanks to a request from my friend Davy (@davidbrustlin) I had a copy of this comic in my house for a few days:

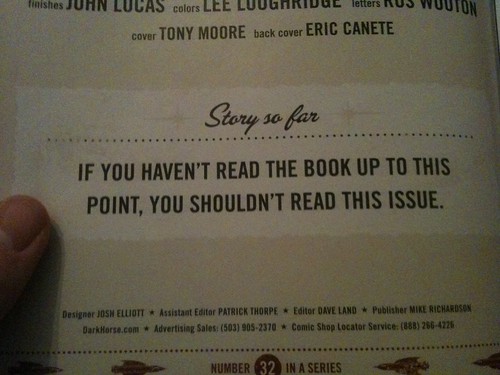

"Fear Agent" #32, the last issue of the series. Now, I am notorious (especially to Davy) for reading (or watching) ahead, skipping over issues (or episodes), and generally 'spoiling' myself on all kinds of developments 'ahead' of me in serial narratives

I rarely find that my enjoyment of a story is ruined by knowing what's happened chronologically further down the river from where I stand in the current. The ideal? No. A disaster? Not really.

So I opened up "Fear Agent" #32...

...and I was delighted to find this message on the inside front cover.

Rick Remender, Tony Moore, and Dark Horse (@DarkHorseComics) are smart gents.

They saw my type coming a mile away:

I read it anyway.

I liked it. A lot.

I found, in "Fear Agent" #32, a story I could mostly understand and although I could not appreciate its connection to the overall structure of the series, I did deeply appreciate its structure as an individual issue. I just plain, old-fashioned, enjoyed it. I followed the conclusion to its main character's emotional arc, felt its resonance in my own life, and was moved by it.

And as I write these words, I'm reading "The Walking Dead" #92 on the NYC subway without having read #14 through #91. I like it, but not a lot.

Not enough to commit to reading the ongoing zombie survival horror epic. Sorry. But still. This is not a bad thing.

I think of it as a test. If I can enjoy this issue for its emotional, storytelling, creative content out-of-context? The creators are doing something right.

So congratulations to writer Rick Remender (@Remender) and artist Tony Moore (@tonymoore). You made me love something. Even without having "read the book up to this point".

~ @JonGorga

"Fear Agent" #32, the last issue of the series. Now, I am notorious (especially to Davy) for reading (or watching) ahead, skipping over issues (or episodes), and generally 'spoiling' myself on all kinds of developments 'ahead' of me in serial narratives

I rarely find that my enjoyment of a story is ruined by knowing what's happened chronologically further down the river from where I stand in the current. The ideal? No. A disaster? Not really.

So I opened up "Fear Agent" #32...

...and I was delighted to find this message on the inside front cover.

Rick Remender, Tony Moore, and Dark Horse (@DarkHorseComics) are smart gents.

They saw my type coming a mile away:

I read it anyway.

I liked it. A lot.

I found, in "Fear Agent" #32, a story I could mostly understand and although I could not appreciate its connection to the overall structure of the series, I did deeply appreciate its structure as an individual issue. I just plain, old-fashioned, enjoyed it. I followed the conclusion to its main character's emotional arc, felt its resonance in my own life, and was moved by it.

And as I write these words, I'm reading "The Walking Dead" #92 on the NYC subway without having read #14 through #91. I like it, but not a lot.

Not enough to commit to reading the ongoing zombie survival horror epic. Sorry. But still. This is not a bad thing.

I think of it as a test. If I can enjoy this issue for its emotional, storytelling, creative content out-of-context? The creators are doing something right.

So congratulations to writer Rick Remender (@Remender) and artist Tony Moore (@tonymoore). You made me love something. Even without having "read the book up to this point".

~ @JonGorga

Another Legend Gone

Filed by

Josh Kopin

on

Friday, December 16, 2011

As much as it saddens me to have to do this, to post about the death of one comics great right after a post about the death of another, I don't really have a choice, since Joe Simon, co-creator of Captain America, passed away on Wednesday. Because I'm in the final throes of the most stressful finals of my life, I don't have the time to spend on a post commemorating Simon the way he deserves, but there'll be one, after the first of year.

In the meantime, here's to you, Joe Simon.

The Gentleman of Comics is Gone

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Saturday, December 10, 2011

People revered Jerry Robinson in our industry because he created The Joker and worked on Batman when he was seventeen years old. I revered Jerry Robinson because he survived our industry with his integrity intact.

He died two days ago, here in New York City.

[via NYCGraphicNovelists.com]

In 1938, he started working for Bill Finger and Bob Kane on Batman as a letterer and assistant inker. A year later, he was inking the book, then naming Robin, on to creating The Joker, Two-Face, and the best butler in popular fiction: Alfred Pennyworth. Soon, he was the key writer, then he switched to penciling the adventures of the Dark Knight.

Later he moved over to newspaper strips, creating two different strips in the 60s and 70s, which in turn led him to two terms as the president of two different nation-wide cartoonists guilds. He next tried his hand as a comics historian, penning a comprehensive history of comics in newspapers.

Most remarkably, in 1975, he and superstar artist Neal Adams secured credit and a lifetime stipend for Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, long-since cast-away. Siegel and Shuster were literally brought in-house and eventually fired from DC after selling them their biggest cash-cow: the first superhero, Superman. Thanks to Adams and Robinson, a small permanent salary was established and their names have been attached to every piece of media featuring Superman ever since. Although even partial ownership rights to their creation was still not granted to them or their families until quite recently, the first steps were made by Adams and Robinson.

In 1978, he upped his commitment to this industry and founded an international syndicate of comics creators, one that still exists today.

This man's accomplishments are not just wide-ranging, not just impressive. Not merely great. They were genuine. They displayed integrity.

When I met Jerry Robinson, very very quickly, in October 2o1o, I was delighted to discover that he was a gentleman. I also learned about his versatility that night: Artist. Writer. Historian. Humanitarian.

Jerry Robinson was an inspiration. A direct inspiration, as I foresee in his legacy a world where comics creators don't have to be cheated out of their rights or their pay.

Losing this man is a loss for us all.

He died two days ago, here in New York City.

[via NYCGraphicNovelists.com]

In 1938, he started working for Bill Finger and Bob Kane on Batman as a letterer and assistant inker. A year later, he was inking the book, then naming Robin, on to creating The Joker, Two-Face, and the best butler in popular fiction: Alfred Pennyworth. Soon, he was the key writer, then he switched to penciling the adventures of the Dark Knight.

Later he moved over to newspaper strips, creating two different strips in the 60s and 70s, which in turn led him to two terms as the president of two different nation-wide cartoonists guilds. He next tried his hand as a comics historian, penning a comprehensive history of comics in newspapers.

Most remarkably, in 1975, he and superstar artist Neal Adams secured credit and a lifetime stipend for Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, long-since cast-away. Siegel and Shuster were literally brought in-house and eventually fired from DC after selling them their biggest cash-cow: the first superhero, Superman. Thanks to Adams and Robinson, a small permanent salary was established and their names have been attached to every piece of media featuring Superman ever since. Although even partial ownership rights to their creation was still not granted to them or their families until quite recently, the first steps were made by Adams and Robinson.

In 1978, he upped his commitment to this industry and founded an international syndicate of comics creators, one that still exists today.

This man's accomplishments are not just wide-ranging, not just impressive. Not merely great. They were genuine. They displayed integrity.

When I met Jerry Robinson, very very quickly, in October 2o1o, I was delighted to discover that he was a gentleman. I also learned about his versatility that night: Artist. Writer. Historian. Humanitarian.

Jerry Robinson was an inspiration. A direct inspiration, as I foresee in his legacy a world where comics creators don't have to be cheated out of their rights or their pay.

Losing this man is a loss for us all.

~ @JonGorga

Defenders Assemble

Filed by

Josh Kopin

on

Friday, December 09, 2011

If there was any question as to whether or not Matt Fraction was the most versatile writer in mainstream comics, Defenders #1 should settle it. In the last year, Fraction added both one of Marvel's flagship books (his Thor is a highpop masterpiece, beautiful and consistently brilliant) and the best event comic in a long time (Fear Itself, which still definitely has its faults) to his bibliography, which already included his work on Casanova, Invincible Iron Man and, my favorite comic of all time, Immortal Iron Fist. Now, with his first year as Marvel's main man behind him, Fraction pulls what could very well be his best single comic ever out of the box; if Defenders follows up on the promise of this first issue, we could have the first great epic of the Modern Age on our hands.

Of course, to give all the credit to Fraction would be a pretty serious sin; this is a great looking book. It has no pretensions towards "high art," it gives no concessions to photorealism; this is high-grade comics art, pure and simple. Terry Dodson's characters move with ease; this art is easiest the supplest I've seen in a long time. There's definitely a certain thrust to his panel designs, and his figures are dynamic even though, as comic art, they're necessarily static. Beyond even that, though, the figures have this marvelous rounded quality; they're cartoony and stylized like what Kirby might have looked like if he had traded blocky for slick. All of this only works, though, because the people finishing up Dodson are so damn good. The inker is his wife, Rachel Dodson, who has to be among the best in the business. Her default line is heavy enough to be noticeable, it's an important part of what gives the art its distinctively slick look, but not so heavy as to be overpowering, and certainly not heavy enough to strangle everything else on the page. This is a very good thing, because colorist Sonia Oback does a very good job of doing a lot with a little. Although a far cry from the "flat" colors that we saw in the pages of Thor: The Mighty Avenger and, more recently, Daredevil, Oback's palate is simple, almost basic, and she doesn't try anything clever: she gives the Dodsons' lines depth, but does a very good job of going just far enough, so that what we get is a comic that looks like a comic, and that doesn't have pretensions towards anything else.

Defenders is an honest book, just trying to be the best comic it can be, and at that it is a magnificent success; that it looks like a comic book should look is only half the reason why (although, too often, it is something that gets overlooked).

Fraction, of course, is the other half. He's helping his art team here: the book does well the things that comics are supposed to do well. It has forward motion, for one, a motion driven by easily readable panel design and a certain artistic thrust, but defined by the general structure and pacing of the comic. Aside from being a clearly distinct narrative, with a distinct three act structure, (note: this sentence so far should probably read "FRACTION'S NOT WRITING FOR TRADE! HOORAY!," but I'm trying to contain my excitement at a writer practicing what should be the basic tenant of comics writing), it gives each protagonist a proper introduction and moment in the spotlight, and sets up a telling internal monologue for each of them, one that emphasizes character in particular contrast to what comes out in the dialogue. This is not to say that the characters don't fit together, or something: the dialogue is an absolute joy, and it seems as natural as anything.

I want to emphasize that, when I use the word "motion," that I'm not just talking figuratively: the way that Defenders moves from place to place literally is impressive (and the panels with the team on the train, with the Surfer outside the window, keeping pace on his board, are AWESOME). Fraction is clearly concerned with it: a surprising percentage of the comic is devoted to it. I'm hoping that it's indicative of a larger tendency towards meditation on the mechanics of what goes on inside the pages of the book, both in terms of the mechanics of the actual plot and in terms of coherence. A comic doesn't have to be perfectly explained to make sense, but the ones that are both (and keep in mind that "perfectly explained" doesn't mean that everything is explained, just the right amount) are few and far between. Fraction is clearly thinking about how his characters get from A to B, and I hope that means that, in the long run, Defenders is going to hang together quite well, that all the pieces are going to fit together and that everything is going to make sense, at least in its proper moment.

That this is a concern which the book diligently does not confirm is impressive, particularly since the premise is that this team that the Hulk is putting together is the team that is going to protect the Marvel Universe from the impossible. One wonders what is impossible in the Marvel Universe, what with its mutant mermen, its sorcerers supreme, its ripped red women, its silver surfers; anything that Fraction throws at this team he's assembled is going to have to boggle the mind. Interestingly, Defenders seems to be aware of its status as a comic book, and I do mean the book itself rather than any of the characters, as they are all blissfully unaware. On the bottom of the pages, though, there are these little messages, advising the reader as to where the story continues and advertising what's going on in a few of the other, perhaps important, Marvel books. A device like this makes me wonder if were in for some kind of meta-adventure, one much more Grant Morrison writing himself into Animal Man than Deadpool's "comic sense."

If we are, there's no team that I would trust to do it more than I trust this one. Defenders is the last essential comic of 2011, and it may also be the first. I haven't been this excited for the second issue of a series in a very long time.

Of course, to give all the credit to Fraction would be a pretty serious sin; this is a great looking book. It has no pretensions towards "high art," it gives no concessions to photorealism; this is high-grade comics art, pure and simple. Terry Dodson's characters move with ease; this art is easiest the supplest I've seen in a long time. There's definitely a certain thrust to his panel designs, and his figures are dynamic even though, as comic art, they're necessarily static. Beyond even that, though, the figures have this marvelous rounded quality; they're cartoony and stylized like what Kirby might have looked like if he had traded blocky for slick. All of this only works, though, because the people finishing up Dodson are so damn good. The inker is his wife, Rachel Dodson, who has to be among the best in the business. Her default line is heavy enough to be noticeable, it's an important part of what gives the art its distinctively slick look, but not so heavy as to be overpowering, and certainly not heavy enough to strangle everything else on the page. This is a very good thing, because colorist Sonia Oback does a very good job of doing a lot with a little. Although a far cry from the "flat" colors that we saw in the pages of Thor: The Mighty Avenger and, more recently, Daredevil, Oback's palate is simple, almost basic, and she doesn't try anything clever: she gives the Dodsons' lines depth, but does a very good job of going just far enough, so that what we get is a comic that looks like a comic, and that doesn't have pretensions towards anything else.

Defenders is an honest book, just trying to be the best comic it can be, and at that it is a magnificent success; that it looks like a comic book should look is only half the reason why (although, too often, it is something that gets overlooked).

Fraction, of course, is the other half. He's helping his art team here: the book does well the things that comics are supposed to do well. It has forward motion, for one, a motion driven by easily readable panel design and a certain artistic thrust, but defined by the general structure and pacing of the comic. Aside from being a clearly distinct narrative, with a distinct three act structure, (note: this sentence so far should probably read "FRACTION'S NOT WRITING FOR TRADE! HOORAY!," but I'm trying to contain my excitement at a writer practicing what should be the basic tenant of comics writing), it gives each protagonist a proper introduction and moment in the spotlight, and sets up a telling internal monologue for each of them, one that emphasizes character in particular contrast to what comes out in the dialogue. This is not to say that the characters don't fit together, or something: the dialogue is an absolute joy, and it seems as natural as anything.

I want to emphasize that, when I use the word "motion," that I'm not just talking figuratively: the way that Defenders moves from place to place literally is impressive (and the panels with the team on the train, with the Surfer outside the window, keeping pace on his board, are AWESOME). Fraction is clearly concerned with it: a surprising percentage of the comic is devoted to it. I'm hoping that it's indicative of a larger tendency towards meditation on the mechanics of what goes on inside the pages of the book, both in terms of the mechanics of the actual plot and in terms of coherence. A comic doesn't have to be perfectly explained to make sense, but the ones that are both (and keep in mind that "perfectly explained" doesn't mean that everything is explained, just the right amount) are few and far between. Fraction is clearly thinking about how his characters get from A to B, and I hope that means that, in the long run, Defenders is going to hang together quite well, that all the pieces are going to fit together and that everything is going to make sense, at least in its proper moment.

That this is a concern which the book diligently does not confirm is impressive, particularly since the premise is that this team that the Hulk is putting together is the team that is going to protect the Marvel Universe from the impossible. One wonders what is impossible in the Marvel Universe, what with its mutant mermen, its sorcerers supreme, its ripped red women, its silver surfers; anything that Fraction throws at this team he's assembled is going to have to boggle the mind. Interestingly, Defenders seems to be aware of its status as a comic book, and I do mean the book itself rather than any of the characters, as they are all blissfully unaware. On the bottom of the pages, though, there are these little messages, advising the reader as to where the story continues and advertising what's going on in a few of the other, perhaps important, Marvel books. A device like this makes me wonder if were in for some kind of meta-adventure, one much more Grant Morrison writing himself into Animal Man than Deadpool's "comic sense."

If we are, there's no team that I would trust to do it more than I trust this one. Defenders is the last essential comic of 2011, and it may also be the first. I haven't been this excited for the second issue of a series in a very long time.

Shortboxes: Defenders, Iron Fist, Marvel, Matt Fraction, Reviews, Terry and Rachel Dodson

Ilias Kyriazis Self-Publishes New Mini-Comic

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Monday, December 05, 2011

Mister Ilias Kyriazis, Greek comicsmith of "Falling For Lionheart" (the graphic novella of last year I had huge anticipation for, really enjoyed, and included on my Best of 2o1o List), has a brand new short comic called "The Dragon And The Ghost" soon to be self-published and available exclusively on his website.

[via Ilias Kyriazis' Google+ account]

Look at this gorgeous thing:

"Falling For Lionheart" was sad, funny, beautiful, enlightening, smart, explosive with action, delightful with romance, and still clear in its main plot-line. Drawn in smooth, simple, cartoony lines, still solid enough to give weight to the characters' realism, and colored vividly and dramatically. Further, the use of the two very divergent styles: slick superhero and rough underground make the story tick in a new beat from one moment to the next.

"Falling For Lionheart" was sad, funny, beautiful, enlightening, smart, explosive with action, delightful with romance, and still clear in its main plot-line. Drawn in smooth, simple, cartoony lines, still solid enough to give weight to the characters' realism, and colored vividly and dramatically. Further, the use of the two very divergent styles: slick superhero and rough underground make the story tick in a new beat from one moment to the next.

The comic is so good, it nearly defies description. And that is only part of why a review of it never appeared here from me. I really should have completed one, because there is not nearly enough awareness of European comics here in the US.

His few comics online are also great. If you're a Beatles fan, prepare for a mind-fuck of a comic in "The One and Only Billy Shears". Marvel at his adaptation "The Iliad in Sixteen Pages". The two pages of POV from within an ancient Greek helmet deserve an award in and of themselves.

"The Dragon And The Ghost" has been previewed here (in Greek) by Comicdom.com and I'm excited even though the article isn't in a language I can read. The comic's promotion is for several reasons... inscrutable.

The opening line of the comic's short description up on the website is:

This is the three-quarter splash page that got me a bit tingly:

Yes, that does appear to be a cavern full of treasures of history, art, and nature. I'm not entirely sure what all that means? At all? But I'm in.

Yes, that does appear to be a cavern full of treasures of history, art, and nature. I'm not entirely sure what all that means? At all? But I'm in.

"The Dragon And The Ghost" mini-comic is available exclusively directly in his online store that opened here yesterday.

~ @JonGorga

[via Ilias Kyriazis' Google+ account]

Look at this gorgeous thing:

"Falling For Lionheart" was sad, funny, beautiful, enlightening, smart, explosive with action, delightful with romance, and still clear in its main plot-line. Drawn in smooth, simple, cartoony lines, still solid enough to give weight to the characters' realism, and colored vividly and dramatically. Further, the use of the two very divergent styles: slick superhero and rough underground make the story tick in a new beat from one moment to the next.

"Falling For Lionheart" was sad, funny, beautiful, enlightening, smart, explosive with action, delightful with romance, and still clear in its main plot-line. Drawn in smooth, simple, cartoony lines, still solid enough to give weight to the characters' realism, and colored vividly and dramatically. Further, the use of the two very divergent styles: slick superhero and rough underground make the story tick in a new beat from one moment to the next.The comic is so good, it nearly defies description. And that is only part of why a review of it never appeared here from me. I really should have completed one, because there is not nearly enough awareness of European comics here in the US.

His few comics online are also great. If you're a Beatles fan, prepare for a mind-fuck of a comic in "The One and Only Billy Shears". Marvel at his adaptation "The Iliad in Sixteen Pages". The two pages of POV from within an ancient Greek helmet deserve an award in and of themselves.

"The Dragon And The Ghost" has been previewed here (in Greek) by Comicdom.com and I'm excited even though the article isn't in a language I can read. The comic's promotion is for several reasons... inscrutable.

The opening line of the comic's short description up on the website is:

"Deep in the forest lives Therr Zon Aakh, the last American dragon."

This is the three-quarter splash page that got me a bit tingly:

Yes, that does appear to be a cavern full of treasures of history, art, and nature. I'm not entirely sure what all that means? At all? But I'm in.

Yes, that does appear to be a cavern full of treasures of history, art, and nature. I'm not entirely sure what all that means? At all? But I'm in."The Dragon And The Ghost" mini-comic is available exclusively directly in his online store that opened here yesterday.

~ @JonGorga

Quote for the Week 12/4/11

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Sunday, December 04, 2011

"It's got unlimited potential. I mean, any art-form where you can use any word in the dictionary-- all the words Shakespeare used, you know, like, he doesn't have a copyright on 'em, you know? You can use any word you want. You can use a vast variety of illustration styles. They're very comparable to movies. I mean, both of 'em use words and pictures."~ Harvey Pekar, the excellent late underground comics writer, in an interview recorded in 2oo8 for a documentary about Jeff Smith, available on YouTube here.

The Improvised Explosive Destruction of Quality of Life

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

"BOOM!", from CartoonMovement.com

A website now exists that is long, long overdue: CartoonMovement.com, a site solely for journalism-webcomics & webcartoons. (With an accompanying Twitter account! @cartoonmovement) The concept of journalism in the form of comics-- pioneered largely by the intrepid Joe Sacco (the comicsmith behind the brilliant and achingly painful "Palestine")-- has finally gone digital and there is fine work being done over there.

For example? The recent post entitled "BOOM!" written by David Axe (@daxe) and drawn by Ryan Alexander-Tanner (@ohyesverynice). A story about a single explosion on a lonely road in Afghanistan. Axe has done a marvelous job of reportage in recounting what it felt like to be isolated with only a few soldiers on a desert road and of the painful alienating effects drifting into his civilian life from the minor brain damage received as a parting gift from the incident. Alexander-Tanner's cartoony style is awkward at times but he translates Axe's experience into his rounded-black-lines-on-white world with grace.

The storytelling is focused and small when it needs to be small and encompasing and large when it needs to be large:

And effectively so.

And effectively so.

The two tiny plates of metal colliding to create the circuit that sends the electricity to the cocktail that ignites and explodes. Action. Reaction. Panel 1. Panel 2.

The storytelling on the next page, in which we experience the explosion a second time, from within the armored vehicle-- and within the outlines of the "BOOM" sound effect-- is masterful. Not only dominating the page, but the six characters present in the main cabin of the vehicle, and the piece as a whole.

We must choose to care about these things, we must put our eyes on the situations unfolding from the choices of the few as they effect the many, no matter how small and seemingly insignificant the effect to one individual's quality of life. Comics like this one help me to do that better.

All of which leads me to the thought: Yes, this is good. Yes, this is important.

All of which leads me to the thought: Yes, this is good. Yes, this is important.

A website now exists that is long, long overdue: CartoonMovement.com, a site solely for journalism-webcomics & webcartoons. (With an accompanying Twitter account! @cartoonmovement) The concept of journalism in the form of comics-- pioneered largely by the intrepid Joe Sacco (the comicsmith behind the brilliant and achingly painful "Palestine")-- has finally gone digital and there is fine work being done over there.

For example? The recent post entitled "BOOM!" written by David Axe (@daxe) and drawn by Ryan Alexander-Tanner (@ohyesverynice). A story about a single explosion on a lonely road in Afghanistan. Axe has done a marvelous job of reportage in recounting what it felt like to be isolated with only a few soldiers on a desert road and of the painful alienating effects drifting into his civilian life from the minor brain damage received as a parting gift from the incident. Alexander-Tanner's cartoony style is awkward at times but he translates Axe's experience into his rounded-black-lines-on-white world with grace.

The storytelling is focused and small when it needs to be small and encompasing and large when it needs to be large:

And effectively so.

And effectively so.The two tiny plates of metal colliding to create the circuit that sends the electricity to the cocktail that ignites and explodes. Action. Reaction. Panel 1. Panel 2.

The storytelling on the next page, in which we experience the explosion a second time, from within the armored vehicle-- and within the outlines of the "BOOM" sound effect-- is masterful. Not only dominating the page, but the six characters present in the main cabin of the vehicle, and the piece as a whole.

We must choose to care about these things, we must put our eyes on the situations unfolding from the choices of the few as they effect the many, no matter how small and seemingly insignificant the effect to one individual's quality of life. Comics like this one help me to do that better.

All of which leads me to the thought: Yes, this is good. Yes, this is important.

All of which leads me to the thought: Yes, this is good. Yes, this is important.You should read it.

~ @JonGorga

~ @JonGorga

Quote for the Week 11/27/11

Filed by

Josh Kopin

on

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Some may chuckle at the notion of Maus as one of a handful of truly indispensable works of post-World War II American literature. American literature since 1945 encompasses Nobel laureates Saul Bellow and Toni Morrison, along with Philip Roth, who if anybody ever listened to me, would already have his Nobel by now. The period also includes the likes of John Updike, John Cheever, Joyce Carol Oates, and Thomas Pynchon, to say nothing of more recent authors such as Tim O’Brien, David Foster Wallace, and Louise Erdrich. Do I seriously mean to compare modern classics like Beloved or Gravity’s Rainbow to a comic book?

In fact I do, and to explain why I need to go back to that community college classroom fifteen years ago. The students in that class were by no means stupid. They weren’t in the least intellectually lazy, either. I find myself annoyed by teachers like the mysterious Professor X, author of In the Basement of the Ivory Tower, who depict their students as lazy, ill-mannered lunks who have no business being in college. This view has no relationship to the reality I encountered in my years teaching in community colleges. After all, those students were giving up their weekends to take an introductory English course. They weren’t saints – I busted a plagiarist in that class, as I recall – but they understood, probably better than the kids in my classes at Fordham University today, that the American dream is built upon education, and they struck me as hungry to get started.

Still, no one in that class was ready for Saul Bellow or, God forbid, Thomas Pynchon. One of the first lessons of teaching literature in the real world is that you have to meet your students where they are, not where you want them to be. In academic jargon, this is called finding your students’ “zone of proximal development,” the sweet spot between what they already know and what they couldn’t possibly comprehend even if you were there to help them. The wonder of Maus is that it fits into everyone’s zone of proximal development. I taught it to those working-class immigrants in California fifteen years ago; I taught it at a third-rate night school in Virginia; and just last month, I taught it in an advanced writing class at Fordham, a prestigious, four-year private university. Every time, in every context, students told me they’d stayed up half the night finishing the book, and then when we discussed it in class, it took the tops of their heads off all over again. Maus is that rare work of literature that speaks to everyone while pandering to no one.

-Michael Bourne, on the importance and power of Art Spiegelman's Maus.

Not Just More Grist For The Mill

Filed by

Josh Kopin

on

Friday, November 25, 2011

I didn't even have a chance to get to the comics to figure out that Mudman was just a little bit different. On the inside cover, just to the right of the indicia (you know, the information about the comic and the publisher, that little bit of a periodical that no one but Jon reads) is a little column written by the comicsmith, like the kind you find just before an old letters page. It's got the same sort of pop-philosophizing that those columns have, the same sort of short, terse, joyful sentences that remind you that rarely does anyone do comics just for the paycheck, that everyone who is in the medium is in the medium because they love comics.

I didn't even have a chance to get to the comics to figure out that Mudman was just a little bit different. On the inside cover, just to the right of the indicia (you know, the information about the comic and the publisher, that little bit of a periodical that no one but Jon reads) is a little column written by the comicsmith, like the kind you find just before an old letters page. It's got the same sort of pop-philosophizing that those columns have, the same sort of short, terse, joyful sentences that remind you that rarely does anyone do comics just for the paycheck, that everyone who is in the medium is in the medium because they love comics.It's pretty clear, from reading that little column, that Paul Grist loves the medium, and not only the medium, but the traditional understanding of the medium, and the medium's traditional delivery system: the comic book, "not," he writes, just to be sure that we understand, "floppies of pamphlets or any of those other slightly derogatory terms that people use to belittle the format." He's not talking, either, about "'sequential art' or any of those other terms folks use when they're trying to be clever about comics," nor is he "Writing for the Trade" or "planning on cramming the collections full of 'DVD extras' like deleted scenes, sketches, and 'directors commentaries.'"

Mudman, then, starts out with a little bit of a manifesto, with an explicit declaration of what it is and what it isn't, with a clear warning: what you have in your hands, says Paul Grist, is nothing or more less complicated or clever than a comic book. It's a pretty bold statement, when you think about, and it's one that's entirely unnecessary: Mudman is a hell of a comic book, the kind that is, actually and despite what Grist might like to claim, quite smart in what it has to say about comics, simply because it does well what comics do well, that is, it tells a story through only the essential parts of that story; everything else is left to the reader to fill in.

All comics, of course, operate in that way; the gutter is what makes comics comics. But Grist uses it particularly well, in part because the story he's beginning to tell, of a young Englishman, Owen Craig, who wakes up one morning and finds that he has the capability to become mud, is as much about the gaps in what happens as it is about what we (and he) know to have happened. The plot comes to us in bits and pieces and, in this way, reflects the way that the medium works. Grist is saying something about comics, and he really is being quite clever about it.

It helps that Grist gives the gutters such an important role on his page: rather than force them towards the edges with too many busy panels, the lines that surrond the action are thick and, although he isn't afraid to draw into them every once in a while, more often they invade the space normally occupied by action than the other way around. What's really impressive about it is he doesn't give a centimeter on this particular principle: the gaps are pretty uniformly twice or three times the size they are in most comics. When he does do something funky, it's a good clue that you're supposed to be paying attention: something outside of the normative boundaries of the universe has happened, or is about to happen. The panels, they really are the world that Grist is building, but there's something intriguingly ephemeral and metaphysical about what surronds it.

And that's all before you get to the art. I've wondered for a long time about Chris Samnee's influences and, if Grist's stuff on Jack Staff looks anything like this stuff here, he has got to be one of them. Mudman's got this great look, blocky and stylized and flat, and the characters move without seeming too loose or slippery. Sometimes it gets hard to tell his characters apart, particularly when they're wearing school uniforms, but that very well may be the point. Another side effect of the gutter-width, perhaps intended and perhaps not, is that the art has room, the characters don't feel cramped even though his art is relatively detailed. What's so amazing about that detail is that there is this preponderance of random seeming lines, but even those add to the art, and, upon closer examination, they make the figures complete.

If there's one thing that seems a little off it's how, on initial reading, the plot seems to barely hang together; there are a few things that just seem to be missing. What's sort of goofy about that, though, is that those holes, rather than being frustrating, draw you back into the book, make it seem really interesting and subtle. Whether or not it all fits together, I suspect everything is going to become clear in the next few issues but, whether or not it does, Paul Grist, by not trying to be clever, by embracing the medium as it was, has put together what may very well be the most interesting and important mainstream comic of 2011.

Variations on a Theme

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Thursday, November 24, 2011

Variant covers. What the fuck, right?

Variant covers. A cultural force all their own? What the fuck, right?

Different covers. But the only difference is... the covers?

So you can choose which one you like. Like the comic inside but hate the cover? Oh, a variant with something less horrible on it. My lucky day!

Or you could do what the publisher, printer, and retailer really want and buy both.

Nobody who steps into my store can make head nor tails of them the first time...

Some people buy almost exclusively variants.

~ @JonGorga

All-New, All-Different

Filed by

Josh Kopin

on

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

I've been reading X-Men comics for a long time. Not as long as some people, of course: I'm barely as old as that massive selling #1 written by Claremont and drawn by Lee, but I've been reading X-Men comics a long time. Long enough that, when I started almost a decade ago, a mediocre writer given to melodrama, Chuck Austen, was writing Uncanny, a certain mad Scot named Morrison was writing New X-Men, and Chris Claremont, a man whose name is probably more closely tied to the group than any other, was writing a book titled (horrifically) X-Treme X-Men. It was, for sure, an odd time for Xavier's merry mutants: the three mainline books were vastly different from one another in not only tone and style, but also in quality. Although I've learned to love Morrison's take above all others from the period, in the moment I loved Austen's Uncanny the best: it had my favorite characters. Now I understand the book to be basically incomprehensible but, when I was thirteen, Austen had me. I loved the melodrama; I loved Angel's angst, I loved that Juggernaut was on the team, I even loved that storyline where Nightcrawler joins the priesthood, only to discover that he was ordained by a bunch of anti-mutant psychos.

All of this is to say, basically, that I'm pretty invested in the X-Men. Except for a two year period during high school, I've been buying and reading X comics pretty consistently for the last nine years; certainly, behind Captain America, they are the major superhero franchise I care about the most and, although I've come close a few times, I've never quite managed to quit them, although I did narrow my purchases from three books to just Uncanny. The last few years have been trying, to say the least, because the writing (from the two writers I hold above all others as the paragons of quality in mainstream superhero comics, Brubaker and Fraction) has been uneven at best and because I was forced to endure the art of Greg Land for a full half of the issues (of course, that the Dodsons did the other half was one of the reasons I hung on for as long as I did). Then, Kieron Gillen took over the book from Fraction and things started to change a little bit. There wasn't a major uptick in quality, at least not immediately, but the books certainly felt different.

All of this is to say, basically, that I'm pretty invested in the X-Men. Except for a two year period during high school, I've been buying and reading X comics pretty consistently for the last nine years; certainly, behind Captain America, they are the major superhero franchise I care about the most and, although I've come close a few times, I've never quite managed to quit them, although I did narrow my purchases from three books to just Uncanny. The last few years have been trying, to say the least, because the writing (from the two writers I hold above all others as the paragons of quality in mainstream superhero comics, Brubaker and Fraction) has been uneven at best and because I was forced to endure the art of Greg Land for a full half of the issues (of course, that the Dodsons did the other half was one of the reasons I hung on for as long as I did). Then, Kieron Gillen took over the book from Fraction and things started to change a little bit. There wasn't a major uptick in quality, at least not immediately, but the books certainly felt different.

And then Schism, a mini with two brilliant ideas and an editorially mandated ending that went on two issues too long, hit.

All the sudden Jason Aaron, he of one of the great crime comics of all time, Scalped, and a Ghost Rider series that is supposed to be very good, despite have been read been read by precisely no one, was writing a book called Wolverine and the X-Men and Gillen was writing a renumbered Uncanny. Despite my distaste for the renumbering, and my ultimate dismissal of the status quo setting mini as utter crap, I have never been more excited to be reading the X-Men.

Let me be very clear about why: both books are hilobrow pop art at their best. This is most obviously true of Aaron's Wolverine and the X-Men: Chris Bachalo's art is, of course, the key here. Bachalo's art is highly stylized, and there's no one in the industry who draws anything like it. The figures are reduced to their necessary components; there are no lines out of place, no extraneous muscles. Visually, the book is to the point, yet, it is, because it uses only those distractions (like the occasional benday dots) that add to the books overall style, incredibly detailed. In terms of story telling, Bachalo uses what we might call functional form; when things are calm, so are the layouts. When things get a little more madcap, the panels go a little crazy. He gets points, too, for his colors, which are understated without being drab; it would have been an easy out to go garish, but instead the book has a dreamy, almost water colored look. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, his designs are fantastic. Although no one receives a serious overhaul, everybody looks just a little bit different, and brilliantly so. In particular, what he's done with Quentin Quire and Beast stands out: the choice to go full throttle on Quire's punk streak is welcome, as is the t-shirt with the red exclamation point, the one he wears underneath his school uniform. As for Beast, well, I don't think I've ever seen such a compact vision of the character, bristling with kinetic energy.

If it sounds like there's a lot going on, there is: in contrast to the slow, melodramatic pacing he's employing on Incredible Hulk, Aaron just sort of throws everything out on the table here and, somewhat miraculously, everything works. There are a hundred ideas going a thousand miles an hour inside Wolverine and the X-Men, and each one is better than the last. The characterizations of Quire and Beast stand out here, too, and I suspect that they're the two to watch the most closely. The additions of an arrogant Shi'ar prince, a mutant born of the Brood and some miniature Nightcrawler-looking things to the cast add just the right amount of mysterious and intriguing to make the whole thing feel worth the energy it takes to read. This is a mad book, which takes its cues from Grant Morrison's time with the extended mutant family; it is, in this way, the inheritor of the best X-Men run of the last twenty years, and maybe of all time. If Aaron can sustain both the energy and the coherence of his first issue over his whole run, he might give Morrison his only proper challenge.

That said, Uncanny is the most exciting its been in a really long time. Kieron Gillen really kicks it into gear with the title's first #1 since the sixties: where Aaron's book is wild, though, this one is reigned in. Although some writers would take the opportunity, when writing a team book with a team that's half ex-supervillains, to do something utterly incomprehensible or suffocatingly moralistic, Gillen makes Cyclops' vision for his team just Machiavellian enough for the enterprise to make sense; it helps that his characterization of Cyclops as the military leader of a sovereign state, inherited from Fraction but perfected since then, is spot on. The rest of the team feels right, too: Magneto, Namor and Emma are, perhaps rightfully, arrogant; Storm's humble power is striking; Colossus and Magik are convincingly tortured. Dr. Nemesis and Danger, two characters who sometimes get short-shrift because they have gone relatively undeveloped except as plot devices, get some of the book's best moments. This is a team book at its best, controlled, except the one place it shouldn't be, that is, the villain, and Mr. Sinister here is a perfect counterpoint to Cyclops and his Extinction team.

That said, Uncanny is the most exciting its been in a really long time. Kieron Gillen really kicks it into gear with the title's first #1 since the sixties: where Aaron's book is wild, though, this one is reigned in. Although some writers would take the opportunity, when writing a team book with a team that's half ex-supervillains, to do something utterly incomprehensible or suffocatingly moralistic, Gillen makes Cyclops' vision for his team just Machiavellian enough for the enterprise to make sense; it helps that his characterization of Cyclops as the military leader of a sovereign state, inherited from Fraction but perfected since then, is spot on. The rest of the team feels right, too: Magneto, Namor and Emma are, perhaps rightfully, arrogant; Storm's humble power is striking; Colossus and Magik are convincingly tortured. Dr. Nemesis and Danger, two characters who sometimes get short-shrift because they have gone relatively undeveloped except as plot devices, get some of the book's best moments. This is a team book at its best, controlled, except the one place it shouldn't be, that is, the villain, and Mr. Sinister here is a perfect counterpoint to Cyclops and his Extinction team.

Although I've been really impressed with Carlos Pacheco's art in the past, here, despite its few flaws, there's something stopping it from transcending from mere high-quality into a kind of brilliance. There's nothing wrong with it, per se, but I do sense that Pacheco is holding back a little bit, perhaps mirroring the control of the writer. I wish he would let loose a little bit; it's a good time to be reading the X-Men, in part because there's nothing conservative about either of the line's new books. If Pacheco begins to take the same chances that Gillen, Aaron and Bachalo have, we could have another brilliant new book on our hands.

All of this is to say, basically, that I'm pretty invested in the X-Men. Except for a two year period during high school, I've been buying and reading X comics pretty consistently for the last nine years; certainly, behind Captain America, they are the major superhero franchise I care about the most and, although I've come close a few times, I've never quite managed to quit them, although I did narrow my purchases from three books to just Uncanny. The last few years have been trying, to say the least, because the writing (from the two writers I hold above all others as the paragons of quality in mainstream superhero comics, Brubaker and Fraction) has been uneven at best and because I was forced to endure the art of Greg Land for a full half of the issues (of course, that the Dodsons did the other half was one of the reasons I hung on for as long as I did). Then, Kieron Gillen took over the book from Fraction and things started to change a little bit. There wasn't a major uptick in quality, at least not immediately, but the books certainly felt different.

All of this is to say, basically, that I'm pretty invested in the X-Men. Except for a two year period during high school, I've been buying and reading X comics pretty consistently for the last nine years; certainly, behind Captain America, they are the major superhero franchise I care about the most and, although I've come close a few times, I've never quite managed to quit them, although I did narrow my purchases from three books to just Uncanny. The last few years have been trying, to say the least, because the writing (from the two writers I hold above all others as the paragons of quality in mainstream superhero comics, Brubaker and Fraction) has been uneven at best and because I was forced to endure the art of Greg Land for a full half of the issues (of course, that the Dodsons did the other half was one of the reasons I hung on for as long as I did). Then, Kieron Gillen took over the book from Fraction and things started to change a little bit. There wasn't a major uptick in quality, at least not immediately, but the books certainly felt different.And then Schism, a mini with two brilliant ideas and an editorially mandated ending that went on two issues too long, hit.

All the sudden Jason Aaron, he of one of the great crime comics of all time, Scalped, and a Ghost Rider series that is supposed to be very good, despite have been read been read by precisely no one, was writing a book called Wolverine and the X-Men and Gillen was writing a renumbered Uncanny. Despite my distaste for the renumbering, and my ultimate dismissal of the status quo setting mini as utter crap, I have never been more excited to be reading the X-Men.

Let me be very clear about why: both books are hilobrow pop art at their best. This is most obviously true of Aaron's Wolverine and the X-Men: Chris Bachalo's art is, of course, the key here. Bachalo's art is highly stylized, and there's no one in the industry who draws anything like it. The figures are reduced to their necessary components; there are no lines out of place, no extraneous muscles. Visually, the book is to the point, yet, it is, because it uses only those distractions (like the occasional benday dots) that add to the books overall style, incredibly detailed. In terms of story telling, Bachalo uses what we might call functional form; when things are calm, so are the layouts. When things get a little more madcap, the panels go a little crazy. He gets points, too, for his colors, which are understated without being drab; it would have been an easy out to go garish, but instead the book has a dreamy, almost water colored look. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, his designs are fantastic. Although no one receives a serious overhaul, everybody looks just a little bit different, and brilliantly so. In particular, what he's done with Quentin Quire and Beast stands out: the choice to go full throttle on Quire's punk streak is welcome, as is the t-shirt with the red exclamation point, the one he wears underneath his school uniform. As for Beast, well, I don't think I've ever seen such a compact vision of the character, bristling with kinetic energy.

If it sounds like there's a lot going on, there is: in contrast to the slow, melodramatic pacing he's employing on Incredible Hulk, Aaron just sort of throws everything out on the table here and, somewhat miraculously, everything works. There are a hundred ideas going a thousand miles an hour inside Wolverine and the X-Men, and each one is better than the last. The characterizations of Quire and Beast stand out here, too, and I suspect that they're the two to watch the most closely. The additions of an arrogant Shi'ar prince, a mutant born of the Brood and some miniature Nightcrawler-looking things to the cast add just the right amount of mysterious and intriguing to make the whole thing feel worth the energy it takes to read. This is a mad book, which takes its cues from Grant Morrison's time with the extended mutant family; it is, in this way, the inheritor of the best X-Men run of the last twenty years, and maybe of all time. If Aaron can sustain both the energy and the coherence of his first issue over his whole run, he might give Morrison his only proper challenge.

That said, Uncanny is the most exciting its been in a really long time. Kieron Gillen really kicks it into gear with the title's first #1 since the sixties: where Aaron's book is wild, though, this one is reigned in. Although some writers would take the opportunity, when writing a team book with a team that's half ex-supervillains, to do something utterly incomprehensible or suffocatingly moralistic, Gillen makes Cyclops' vision for his team just Machiavellian enough for the enterprise to make sense; it helps that his characterization of Cyclops as the military leader of a sovereign state, inherited from Fraction but perfected since then, is spot on. The rest of the team feels right, too: Magneto, Namor and Emma are, perhaps rightfully, arrogant; Storm's humble power is striking; Colossus and Magik are convincingly tortured. Dr. Nemesis and Danger, two characters who sometimes get short-shrift because they have gone relatively undeveloped except as plot devices, get some of the book's best moments. This is a team book at its best, controlled, except the one place it shouldn't be, that is, the villain, and Mr. Sinister here is a perfect counterpoint to Cyclops and his Extinction team.

That said, Uncanny is the most exciting its been in a really long time. Kieron Gillen really kicks it into gear with the title's first #1 since the sixties: where Aaron's book is wild, though, this one is reigned in. Although some writers would take the opportunity, when writing a team book with a team that's half ex-supervillains, to do something utterly incomprehensible or suffocatingly moralistic, Gillen makes Cyclops' vision for his team just Machiavellian enough for the enterprise to make sense; it helps that his characterization of Cyclops as the military leader of a sovereign state, inherited from Fraction but perfected since then, is spot on. The rest of the team feels right, too: Magneto, Namor and Emma are, perhaps rightfully, arrogant; Storm's humble power is striking; Colossus and Magik are convincingly tortured. Dr. Nemesis and Danger, two characters who sometimes get short-shrift because they have gone relatively undeveloped except as plot devices, get some of the book's best moments. This is a team book at its best, controlled, except the one place it shouldn't be, that is, the villain, and Mr. Sinister here is a perfect counterpoint to Cyclops and his Extinction team.Although I've been really impressed with Carlos Pacheco's art in the past, here, despite its few flaws, there's something stopping it from transcending from mere high-quality into a kind of brilliance. There's nothing wrong with it, per se, but I do sense that Pacheco is holding back a little bit, perhaps mirroring the control of the writer. I wish he would let loose a little bit; it's a good time to be reading the X-Men, in part because there's nothing conservative about either of the line's new books. If Pacheco begins to take the same chances that Gillen, Aaron and Bachalo have, we could have another brilliant new book on our hands.

Quote for the Week 11/20/11

Filed by

Josh Kopin

on

Sunday, November 20, 2011

"Thing is, I really like comics. Now, when I say comics, I'm not talking about 'sequential art' or any of those other fancy terms folks use when they're trying to be clever about comics. I'm talking about 32 pages of folded paper together with a couple of staples. Comics. Not floppies or pamphlets or any of those other slightly derogatory terms that people use to belittle the format. Comics."-Paul Grist, on the first page of the first issue of his Image comic Mudman, convincing me to put it on my pull-list even before I've read the damn thing.

Limited Risk

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Saturday, November 19, 2011

Tom Brevoort, Senior Vice-President of Publishing & Executive Editor at Marvel Comics (@tombrevoort), wrote this on his Formspring account, in answer to "re: Destroyers: Is Marvel now preemptively cancelling yet-to-be-solicited books based on anticipated sales?":

"Not exactly. We've been saying for months now that we're going to be putting out fewer limited series, and instead focusing on our core monthly titles in response to where the marketplace seems to be right now. That's what we're doing. And that means that some projects that were initiated earlier are going to fall by the wayside. But at least among the best of those in terms of ideas, there's nothing saying that we can't revisit them later if conditions change." (His account is here at formspring.com/tombrevoort)

Not sure this bodes well for much of anything... Is he doing a bit of damage control on the several cancelled minis of late? Is he presenting us a 'new economy' policy? Both?

Limited series, mini-series, maxi-series, whatever you want to call them are the place where larger companies like Marvel (@MARVEL) experiment. As such, it's where the next great series comes from. "Luke Cage: Noir" was four issues that made it to my '2oo9 Best of the Year' list. "Marvel 1602", although not a favorite of mine, has made the company a lot of dough and brought a lot of fans of Neil Gaiman (@neilhimself) to the Marvel corporate characters in a sideways manner.

Minis are a very good thing. Less of them is potentially a very bad thing. But, as always, if it's really a matter of saving absolutely required green to keep the company moving to keep bringing out more comics later... then I'm for it.

~ @JonGorga

What Makes the Art Sequential?

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Sunday, November 13, 2011

"Being in a sequence," you're probably saying to yourself after reading that title.

I posted this on Flickr recently:

So... is it comics?

A few nights ago at the house of someone who's work I'm editing I was reacquainted with my Bard College senior project. I'd e-mailed it to her on request months ago and she printed it out. I wrote over two years ago:

I posted this on Flickr recently:

So... is it comics?

A few nights ago at the house of someone who's work I'm editing I was reacquainted with my Bard College senior project. I'd e-mailed it to her on request months ago and she printed it out. I wrote over two years ago:

"In his ground-breaking book with a textbook approach to explaining comics, Comics and Sequential Art, Will Eisner defined comics immediately as “the arrangement of pictures or images and words to narrate a story or dramatize an idea” but then far more simply as “Sequential Art” (Eisner 5) i.e. visual art in sequence. Scott McCloud followed Eisner’s lead in his own Understanding Comics when he put forth his suggestion for a dictionary definition of comics: “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer” (McCloud 9) and continued in the following pages of Understanding Comics to demonstrate how his definition broadened the world of comics both historically (McCloud 10-17) and artistically (McCloud 18-20) by demonstrating that many things were comics, simply because many things had not appeared to be comics by old, restrictive perceptions. This thesis borrows McCloud’s definition, attempting to simplify it nearer to Eisner’s compact version, synthesizing them to: visual art in deliberate sequence to create meaning. McCloud’s “juxtaposed” is the first to go as there are several kinds of juxtaposition in comics (left to right panels, top to bottom panels, pages left to right) and not all are key to the medium, McCloud’s “pictorial and other images” falls under the umbrella of “visual art”, McCloud’s “deliberate sequence” is the most important part of his definition, as images in sequence are to be found in a few cases that are not comics but not in deliberate order, and is thus retained exactly, and McCloud’s “convey information and/or produce an aesthetic response in the viewer” can be summed up as the creation of informational/aesthetic “meaning.” Simpler, more concise, and more accurate: visual art in deliberate sequence."

Putting images into a sequence. Is it enough?

~ @JonGorga

~ @JonGorga

Quote for the Week 11/10/11

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Thursday, November 10, 2011

"I had only the germ of an idea for Lentil. It started out as just a lot of pictures of a boy playing the harmonica. I didn't have any idea whether I was going to have words with my pictures or not. I thought the drawings might lead to a series of lithographic prints, not necessarily to a children's book at all. But once there got to be some words, the words grew and then the pictures grew."~ Robert McCloskey, children's book creator, in an interview with Leonard S. Marcus as collected in "Ways of Telling: Conversations on the Art of the Picture Book", page 109.

[Brought to my attention by my friend and collaborator Ellen Stedfeld (@Ellesaur).]

Seeing SuperMen and Women As They Were

Filed by

Jon Gorga

on

Tuesday, November 08, 2011

So the new DC Universe has launched. The first month of new series and newly re-launched series has passed and the shared fictional universe inhabited by the DC superheroes 'will never be the same'. Sorta-kinda-not-really.

So the new DC Universe has launched. The first month of new series and newly re-launched series has passed and the shared fictional universe inhabited by the DC superheroes 'will never be the same'. Sorta-kinda-not-really.[Josh has already reviewed two of the re-launching books "Justice League" #1 and "Wonder Woman" #1, and I intend to review at least one of them myself, but here I'm trying to take a big-picture outlook on this relaunch and the superhero characters at its center. This is a snapshot, a time-capsule, of the moment before long-time superhero reader Jon Gorga has read a single one of DC's New 52 issues.]

The truth is that this is far from the first time these characters have been reinvented. (1986's "Crisis on Infinite Earths", most notably.) The highest-profile retro-fitting maybe. Mentioned in newspapers. Advertised on TV. But still. As I've written before, these long-running pop culture characters have to be treated like rubber bands. Stretch! Stretch who these characters can be! Make Ray Palmer, the superheroic, super-shrinking Atom, a widower to a crazy serial killer. (That was done back in 2oo5 in the near-universally-revered mini-series "Identity Crisis".) Make Batman and Superman aging neo-fascists. (Frank Miller seemed to have no fear in pushing that concept in his works "The Dark Knight Returns" and "The Dark Knight Strikes Again".) Place Superman's famous crash-landing in the corn fields of the USSR instead of the US circa 1938. ("Red Son", Mark Millar's alternate take on the DC mythos is also a popular one.)

Over these past weeks of reading and rereading, I've (re)encountered:

4 versions of Wonder Woman

9 versions of Superman

and

25 versions of Batman...

9 versions of Superman

and

25 versions of Batman...

plus:

3 versions of the Martian Manhunter

2 versions of the Flash

2 versions of Green Arrow

3 versions of the Question

And so on...

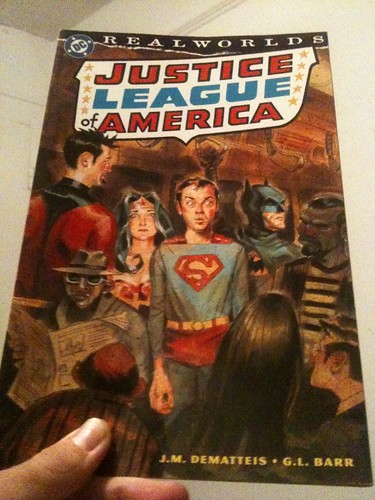

I finished reading all the non-continuity Elseworlds stuff sitting around my house from Frank Miller's goddamn Batman to J.M. DeMatteis' Realworlds TV producer Batman to Warren Ellis' interpretation of Adam West's Batman to Brian Azzarello's First Wave Batman to the kiddie Batman from "Batman: Brave and the Bold".

I finished reading all the non-continuity Elseworlds stuff sitting around my house from Frank Miller's goddamn Batman to J.M. DeMatteis' Realworlds TV producer Batman to Warren Ellis' interpretation of Adam West's Batman to Brian Azzarello's First Wave Batman to the kiddie Batman from "Batman: Brave and the Bold".Then I moved onto the origins of these fantastic characters: "Batman: Year One", "Superman For All Seasons", "Superman: Earth One" (which I reviewed when it came out last year), "Superman: Secret Origin", "DC: The New Frontier".

I followed this with two issues of "Justice League of America" circa late 1973 I've had sitting around for a very long time. #107 and #108, which make-up "Crisis on Earth-X!" specifically. And I chose to finish in entirely unfamiliar territory: a copy of Jack Kirby's "OMAC" #6.

The result? A whole mess of Batmen, actually. I realized that my first childhood favorite was still my favorite among the DC pantheon and the amount of his appearances among my reading material from the company belied this.

But in that, I discovered something about all these different interpretations of the character: they are all completely different but they all have something in common. Something that makes them all still qualify as Batman.

From Warren Ellis' original pitch for the one-shot "Planetary/Batman: Night on Earth":

Same sentiment said faster, perhaps, by Brian Azzarello (@brianazzarello) in "Batman/Doc Savage: Bronze Night" one-shot:

"The Batman sees how to end it -- and tells Blank how to see the world. What worked for him when he's teetered on the edge. How to perceive the world." Batman, the man who "tries to make the world make sense by thinking about it..." (Batman/Planetary Deluxe Edition, p. 50)From the script to the same:

"[Elijah] SNOW; YOU'RE NOT A COP ARE YOU?

SNOW; I DON'T THINK VIGILANTE IS THE RIGHT WORD, EITHER.

...

BATMAN; DO YOU REMEMBER YOUR PARENTS?

BLACK; YES.

...

BATMAN; DO YOU REMEMBER TIMES WHEN THEY MADE YOU FEEL SAFE?

BLACK; YES.

...

BATMAN; THAT'S WHAT YOU HOLD ON TO.

BATMAN; THAT'S WHAT YOU CAN DO FOR OTHER PEOPLE.

BATMAN; YOU CAN GIVE THEM SAFETY. YOU CAN SHOW THEM THEY'RE NOT ALONE.

PAGE FORTY-SIX

Pic 1;

A half-page portrait of the Batman, head and shoulders -- THIS is the reason he does what he does. This is the lost core of the man.

BATMAN; THAT'S HOW YOU MAKE THE WORLD MAKE SENSE.

BATMAN; AND IF YOU CAN DO THAT --

BATMAN; -- YOU CAN STOP THE WORLD FROM MAKING MORE PEOPLE LIKE US." (Batman/Planetary Deluxe Edition, pgs. 91-94)This got my wheels spinning... Batman changes his point-of-view through sheer willpower and that altered POV is absolutely required to do "what he does"? If Warren Ellis (@warrenellis) says it, it must be true!

Same sentiment said faster, perhaps, by Brian Azzarello (@brianazzarello) in "Batman/Doc Savage: Bronze Night" one-shot:

"I know I can make the world better. ... Hell, from before I could think for myself, that's all I thought to do." (Batman/Doc Savage Special, pgs. 4-5)

In "The Dark Knight Strikes Again", on his return to Earth after a very long sojourn, at Batman's request, Hal Jordan the Green Lantern thinks:

"How strange that it would be you. The mean one. The cruel one. The one with the darkest soul. ... How strange that you, of all of us, would prove to be the most hopeful."(The Dark Knight Strikes Again Deluxe Edition, p. 202)

"The Dark Knight Strikes Again" really should be titled something like "The Justice League Returns" as it's more of an ensemble piece than the name suggests.

Furthermore, a careful reading of Neil Gaiman's (@neilhimself) "Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader?" brings us a parallel as the supposedly dead Batman speaks to his long-dead mother Martha Wayne:

"You don't get heaven, or hell. Do you know the only reward you get for being Batman? You get to be Batman." (Detective Comics #853, p. 19)Perhaps a better selection from that work, that comes closer to the meat of the answer I want, is:

"I've learned... that it doesn't matter what the story is, some things never change.

...

The Batman doesn't compromise. I keep this city safe..." (Detective Comics #853, p. 12)

Batman is the man who makes the world a better place by altering his point of view.

But what about those other two heroes of DC's holy trinity?

Superman seems so simple on the surface that most discount him entirely. 'Superman isn't brave, he's invulnerable', I've heard people say. This is a mistake.

Superman is vulnerable in that he is too emotional, too nice. Too perfect.

Frank Miller's "The Dark Knight Strikes Again" presents Superman as a man broken by the yoke of his own fears. A superhuman so afraid of any loss of human life, he allows for a complete destruction of the quality of all life.

The sequel to "The Dark Knight" quadrology from 1986 is almost universally reviled among comics-fans. It's a tremendously dark and depressing portrayal of the DC Comics superhero characters. In the end, Superman is convinced by the daughter he has had with Wonder Woman as well as Miller's fascist Bruce Wayne that the remaining superheroes ARE categorically different, ontologically different, and unquestionably better than petty, average, normal human beings. So why NOT rule over them and force them to live better lives? Millar's Emperor Superman from his "Red Son" comes to the exact same conclusion: be the alien overlord, force the peons to be good.

The sequel to "The Dark Knight" quadrology from 1986 is almost universally reviled among comics-fans. It's a tremendously dark and depressing portrayal of the DC Comics superhero characters. In the end, Superman is convinced by the daughter he has had with Wonder Woman as well as Miller's fascist Bruce Wayne that the remaining superheroes ARE categorically different, ontologically different, and unquestionably better than petty, average, normal human beings. So why NOT rule over them and force them to live better lives? Millar's Emperor Superman from his "Red Son" comes to the exact same conclusion: be the alien overlord, force the peons to be good.In the movie "Kill Bill:Vol. 2", David Carradine gives a soliloquy on the nature of Superman in the middle of a fight scene with Uma Thurman. Quentin Tarantino very smartly cribbed from Jules Feiffer's famous essay "The Great Comic Book Heroes" when he had the character of Bill say:

"Superman didn't become Superman. Superman was born Superman. When Superman wakes up in the morning, he's Superman. His alter ego is Clark Kent. His outfit with the big red "S", that's the blanket he was wrapped in as a baby when the Kents found him. Those are his clothes. What Kent wears - the glasses, the business suit - that's the costume." ("Kill Bill: Vol. 2", 2oo4)

So:

Superman is the secret identity.

Clark Kent is the disguise.

But:

Clark Kent is the everyman.

And Superman is like no man.

Emotionally and psychologically very human but ontologically alien. Biologically Kryptonian. Somewhere in-between is the real person, Kal-El. The Superman, the Ubermench, the In-Between Man. He may not be the everyman, but he is of every person who's ever lived.

Somebody wise once wrote: Batman is a man trying to be a god, Superman is a god trying to be a man.

I think that's the truth. Just not the whole truth. They are both men and both gods, both effect change in a positive way, but from different sources of energy.

-Superman is 'good' striving forward, positively

-Batman is 'bad' striving forward, positively.

That's why Batman appeals to people who find the Superman character repulsively simple, while Superman fans rarely fail to be Batman fans also. Batman took negative energy, used it, and spun it positively. Parents murdered in front of him at an early age. So he struggles to fight so that none may have to experience what he did. Superman took positive energy and spread it exponentially. He was shown kindness by his adopted planet from day one, despite his great loss in never knowing his birth parents, his birth home. He struck out to make others feel as welcomed and safe as he was.

So then...

Is Wonder Woman just a female clone of Superman? Just more good vibrations? A god trying to be a woman? It's been suggested that as she is the enemy of Ares, and thus the enemy of War, she is the peace-maker of the DC pantheon. ("Super Heroes United!: The Complete Justice League History", Justice League: The New Frontier DVD, 2oo8) Yes, but they are all peace-makers! I think Wonder Woman might be among the clearest examples of what all mythic characters are at their core: ideas striving to be alive. Womanhood. Strength in femininity. Fortitude in the face of social-bondage.

And Superman is like no man.

Emotionally and psychologically very human but ontologically alien. Biologically Kryptonian. Somewhere in-between is the real person, Kal-El. The Superman, the Ubermench, the In-Between Man. He may not be the everyman, but he is of every person who's ever lived.

Somebody wise once wrote: Batman is a man trying to be a god, Superman is a god trying to be a man.

I think that's the truth. Just not the whole truth. They are both men and both gods, both effect change in a positive way, but from different sources of energy.

-Superman is 'good' striving forward, positively

-Batman is 'bad' striving forward, positively.

That's why Batman appeals to people who find the Superman character repulsively simple, while Superman fans rarely fail to be Batman fans also. Batman took negative energy, used it, and spun it positively. Parents murdered in front of him at an early age. So he struggles to fight so that none may have to experience what he did. Superman took positive energy and spread it exponentially. He was shown kindness by his adopted planet from day one, despite his great loss in never knowing his birth parents, his birth home. He struck out to make others feel as welcomed and safe as he was.

So then...

Is Wonder Woman just a female clone of Superman? Just more good vibrations? A god trying to be a woman? It's been suggested that as she is the enemy of Ares, and thus the enemy of War, she is the peace-maker of the DC pantheon. ("Super Heroes United!: The Complete Justice League History", Justice League: The New Frontier DVD, 2oo8) Yes, but they are all peace-makers! I think Wonder Woman might be among the clearest examples of what all mythic characters are at their core: ideas striving to be alive. Womanhood. Strength in femininity. Fortitude in the face of social-bondage.

And what of these other men and women with remarkable abilities?

The Flash has been portrayed as a man running away from his past and/or toward solutions. The Martian Manhunter feels like an old soldier brought into a new fight. Green Arrow is the superhuman social conscience. Black Canary is the superheroic working woman. Green Lantern is a bureaucratic superhero, a space-cop who has to answer to the intergalactic Guardians. The Question is the spiritual warrior.

I believe, now, what I've always believed: superheroes are an intrinsic part of the human psyche exploded and clarified, expanded into colorful representations of our desires, our needs, our hopes, and our dreams. DC was there first and, in some ways at least, did it best. And I suspect no re-boot, re-launch or re-imagining will change that.

P.S. ~ I'm looking forward to reading some non-DC comics for the first time in roughly two months...

Shortboxes: Batman, Brian Azzarello, DC, DC Relaunch, Editorial, Frank Miller, Green Lantern, Neil Gaiman, Superman, Warren Ellis, Wonder Woman

Words and Pictures with Jason Latour

Filed by

Josh Kopin

on

Friday, October 21, 2011

At last weekend's New York Comic Con, I did some reporting for Bleeding Cool. They were kind enough to let me mirror some of the interviews that I did for them here at THE LONG AND SHORTBOX OF IT! This is one of Jon's favorite upcoming creators, Jason Latour, talking about his writing on the nonnoir Loose Ends and how his process is changed because he is both a writer and an artist. It was originally posted to Bleeding Cool on 10/16/11

JK:Will you tell me a little bit about Loose Ends?