In November, Image is reissuing Scene of the Crime, Ed Brubaker's first collaboration with Michael Lark, who would later draw much of the writer's supreme Daredevil run. Lark is a fantastic illustrator of crime comics, one of the best in the business, and the fact that he's inked here by Sean Phillips, another longtime Brubaker pal and maybe the best crime cartoonist right now, can only mean good things. If this book is half as good as those Daredevil comics or a quarter as good as Brubaker and Phillips' work on Fatale, Incognito, and Criminal, we're looking at one of the best reissues of the year.

The Criminals Always Return To The...

Filed by

Josh Kopin

on

Friday, August 17, 2012

In November, Image is reissuing Scene of the Crime, Ed Brubaker's first collaboration with Michael Lark, who would later draw much of the writer's supreme Daredevil run. Lark is a fantastic illustrator of crime comics, one of the best in the business, and the fact that he's inked here by Sean Phillips, another longtime Brubaker pal and maybe the best crime cartoonist right now, can only mean good things. If this book is half as good as those Daredevil comics or a quarter as good as Brubaker and Phillips' work on Fatale, Incognito, and Criminal, we're looking at one of the best reissues of the year.

The Colorist As Unsung Hero

Filed by

Josh Kopin

on

Monday, August 13, 2012

Although many comics, including a vast majority of superhero comics, are collaborative efforts, the major share of the credit for such books goes to the writer and the penciler. It's their names on the front, and when big announcements are made when creative teams change, those are the folks that everybody wants to know about. For a while, though, I've been toying with the idea that a colorist can either cement the look and tone that the penciler was going for or, even with the best of intentions, he or she could ruin it. Cartoonist Scott Kurtz, who's behind the long running webcomic PvP, recently made a change to his comic that is demonstrative of how important coloring can be.

Although PvP was originally a black and white comic which utilized color only occasionally, for the last two or three years Kurtz has self-colored his comics. Here, for example, is his strip from Thursday, August 2nd:

One of the joy's of PvP is the way that Kurtz has, over his comic's fourteen year run, managed to maintain a very simple look, one that is clean and flat. In part, this is because Kurtz relies on his pen rather than his colors to add depth and perspective to his panels, so, while Kurtz often and successfully takes risks with his pencils, he rarely makes similarly risky decisions with his crayons, so to speak. When he does, the results are usually strips like the one above. If you look, in the first panel, at Max Powers's hair (Max is the blonde one, in the middle) or Lucille's face, you can tell that both are sort of off-colored, paler than they are in the other panels, bluish almost. I think Kurtz was trying to give his panel the feel of the club the three characters are in, but he can't quite pull it off-- look at Lucille's shirt in that first panel, or at wholes of the other two panels. It sort of looks like Kurtz gave up on the idea of a "club feel" two thirds of the way into the first part of the sequence, and decided to rely instead on the background alone to indicate setting. And so the strip, while not bad, exactly, is more muddled than Kurtz's usual work, which has this wonderful pop off of the screen.

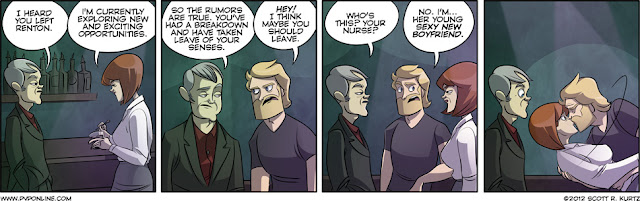

The next day (8/3), Kurtz utilized a colorist other than himself:

Kurtz decided to ask Mary Cagle, his onetime intern and the proprietor of the webcomic Kiwi Blitz, to do the coloring while he worked on building a strip buffer, so the differences in color are individual artistic choices rather than a conscious adjustment, but I think they're demonstrative anyway. You can see, for example, the way that the color tones on the faces changes slightly as the characters move around inside the three dimensional space represented by the two dimensional panel. This solves the problem that Kurtz had encountered the day before, and I think that the punchline panel is actually much subtler and more effective than it would have been if Kurtz had colored it. Much more importantly for the general appearance of the comic, however, is the fact that Cagle uses shadow in a way that Kurtz doesn't, imagining an off panel light source and then changing the tones on certain parts of the figures (again, look at the faces), which gives the panels a lot more depth than Kurtz's colors do, at the cost of some of his pop.

I want to reiterate that, while the timing of the coloring changeover fixed a certain problem that Kurtz was having with a specific setting, I generally think he's a very good colorist, particularly because he made his strip in black and white for almost a decade before switching over to color on a regular basis and somehow managed to keep the strip feeling the same after the switch-- simplicity in coloring goes a long way. Cagle, too, is very good, and, because neither Kurtz's nor Cagle's color work is peculiar or distracting, a preference for one or the other ia a simple matter of taste. For what's its worth, I actually think that I like the former better than the latter, if only because, somewhat ironically, the realism that Cagle adds by making the panels deeper makes some of Kurtz's character design less amusing, and more sort of bulbous and silly. Whichever one you prefer, though, there's little doubt that color changes the strip, changes the way pencils are perceived. Those pencils might be direct a comic's look, but the color confirms it, and a good color artist can rescue a poorly drawn strip the same way that a poor colorist could ruin a good one.

I want to reiterate that, while the timing of the coloring changeover fixed a certain problem that Kurtz was having with a specific setting, I generally think he's a very good colorist, particularly because he made his strip in black and white for almost a decade before switching over to color on a regular basis and somehow managed to keep the strip feeling the same after the switch-- simplicity in coloring goes a long way. Cagle, too, is very good, and, because neither Kurtz's nor Cagle's color work is peculiar or distracting, a preference for one or the other ia a simple matter of taste. For what's its worth, I actually think that I like the former better than the latter, if only because, somewhat ironically, the realism that Cagle adds by making the panels deeper makes some of Kurtz's character design less amusing, and more sort of bulbous and silly. Whichever one you prefer, though, there's little doubt that color changes the strip, changes the way pencils are perceived. Those pencils might be direct a comic's look, but the color confirms it, and a good color artist can rescue a poorly drawn strip the same way that a poor colorist could ruin a good one.

Here's To You, Joe Kubert

Filed by

Josh Kopin

on

Sunday, August 12, 2012

It's been a bad year for the elder statesmen of comics. Back in December, we lost Jerry Robinson and Joe Simon within days of each other and, today, Joe Kubert passed away at the age of 85. I can't say that I'm particularly familiar with Kubert's work, unfortunately, except for a Sgt. Rock collaboration written by Brian Azzerello. That book, though, Between Hell and a Hard Place, is one of my favorite graphic novels, a very honest sort of war story made all the better by Kubert's feeling impressionism. He handled all the visual elements of the work himself, and the soft lines and light colors come together to give the book a sort of distant, gauzy feel, one that contrasts with the way his storytelling ability drives home just how serious of a work Between Hell and a Hard Place and its horrific subject really are. Kubert, who served in Korea, very clearly knew that the way we remember the Second World War and the way it actually was are two very different things, and, in evoking both, his artwork reveals the flaws inherent both in an idealized view of history and in a sanitized account of the violence of war.

Because I love Between Hell and a Hard Place so much, I always sort of figured I'd take in some more of his work sooner or later and, while its never too late to dig deeper, my reading of his work will now always be marked with a certain cheapness, a certain sadness, the spectre of the fact that I started to read Joe Kubert's life work because he had died before I could get around to it. Which is not to say that I won't start in, just the opposite. It just won't be the same as it would have been if I had read it before today.

Move easy, Joe. You'll be missed.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)