Webcartoonist Dylan Meconis has gone and said some very clever things about the mistakes non-comics people make when they attempt to review comics. You should go read the whole piece, I think so highly of it that I'm going to link to it again, but I want to highlight something she says about a topic that Jon and I have been tracking for a while, namely, the Major Semantic Question of Comics, the great comic book/graphic novel debate. Like any good rhetorician, Meconis first defines her terms:

As comics people, we need to get over that attitude if we ever want to be taken seriously, if we ever want not-comics people to be capable of writing good comics criticism. In some ways, it's about wiping a peculiarly weak kneed kind of arrogant elitism off of our shoulders. Mostly, though, it's about reading comics on the subway or talking about them to your parents or teachers, and it's about calling them what they are when you do; it's about time we walk into the yellow benday dots of sunlight, our four colored flag raised high.

Comics (generally singular, despite the s) is the medium. You may also (though much less frequently) hear sequential art.

A comic is any complete work in the comics medium, regardless of genre or length. Rather like “film” or “poem.”

A comic book is, for the sake of definition, any complete work made in the comics medium that is long enough to involve several pages of material or have a collective title. If it were printed, would you have to staple it to keep it all together? Great. Let’s call it a comic book, then.

A graphic novel is a complete work of fiction in the comics form which, if printed, is long enough to be bound as a trade volume, so with a glued or sewn spine. (How’s that for arbitrary?) It is a novel, just as Jane Eyre is a novel, but it is told in comics, not prose.This is a pretty good set of definitions; I particularly like how she categorizes in part by the kind of binding, which is not something I had seen before; it seems rather useful. Still, these categories are slightly flawed, because they don't distinguish between works that were conceived of and published as singular works which could be read in one sitting (Blankets) and collections of material that was originally published serially (those great Fantagraphics Peanuts collections, almost every book with a glued or sewn spine put out by Marvel, DC, Image, Dark Horse, etc). That Meconis doesn't make this distinction, however, is probably smart; she's teaching a correspondence course, and the fact that the two above categories seem similar but are actually fundamentally different is probably a lecture for comics 302. The point she goes on to make is far more important than that (read: my) particular hobby horse:

“Graphic novel” is basically a very clever marketing term that allows booksellers, librarians, and other nervous adults to have a shorthand for “book-length thing of comics that we can sell for over ten dollars and doesn’t make you look like a pedophile for reading in public.” Unlike many people in the comics business, I don’t mind the (fairly new) term, because it’s done great things to convince people who aren’t avid comics readers that it’s okay to pick up a comic book now and again without fearing their book group’s scorn.This is close to right, but I've got a small quibble: "graphic novel" isn't basically a marketing term, it is a marketing term. Formally, graphic novels aren't distinct from comics in any meaningful way; as she says, the only real difference has to do with length and presentation. And a bigger quibble: I understand what Meconis is saying when she explains why she doesn't mind the term "graphic novel," but I would probably argue that the whole of the argument, its mere existence, is just a serious instance of her rule seven (This Muffin Is So Good It Must Be a Bagel, see here for another, particularly insipid, example), one that's so pervasive that it effects even comics people. I can see no reason to call comics something other than comics. That's what they are. I understand that the term "graphic novel" is useful as a marketing term, but it is only used at all because, as Meconis says, it gets people to take the form seriously. But when we're groping for phrases, like "graphic novel" or, worse, "sequential art," which correctly places comics in a particular tradition of serial art but then also tries to retroactively claim that works in that tradition are themselves comics, that seem to legitimize what we read, we're actually just presenting a defensive posture that says that we, too, are uncomfortable loving these weird fusions of picture and text, that we are uncomfortable loving a form that is often dismissed out of hand despite a maturation that's been ongoing for more than a century. Basically, because we've been cowed into being timid about what we love, when we're confronted by a skeptic we revert to an easy semantic out: "Oh, no. This isn't some lowbrow comic book! Why, it's a graphic novel!," rather than attempting to suggest comics are worthwhile, on their own terms, by presenting examples.

As comics people, we need to get over that attitude if we ever want to be taken seriously, if we ever want not-comics people to be capable of writing good comics criticism. In some ways, it's about wiping a peculiarly weak kneed kind of arrogant elitism off of our shoulders. Mostly, though, it's about reading comics on the subway or talking about them to your parents or teachers, and it's about calling them what they are when you do; it's about time we walk into the yellow benday dots of sunlight, our four colored flag raised high.

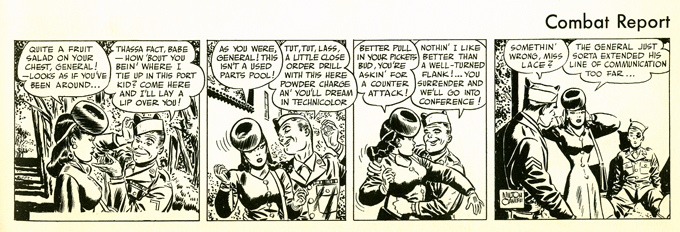

.JPG)